Your full-service corporate communications partner

Trusted by leading international companies

about Stampa

Strategic advice, with flawless execution

International outlook

We offer you a global perspective with local expertise, thanks to our experienced international team, based in Amsterdam, London and Brussels.

Native experts

We speak your language, with multi-lingual communications skills, including native English and Dutch, and extensive on-the-ground knowledge of Benelux and British media.

PR leader in Benelux

You’re in safe hands – we’re the leading independent PR agency in the Benelux, trusted by blue-chip clients in finance, energy, technology, and other sectors.

Former top-level journalists

You can be sure we know what works for the media and how the media works – many of our team are former journalists from top-tier media organisations.

From internal to external

We can support your full range of corporate communications, from internal communications to external PR and stakeholder engagement.

Creative ideas and execution

We know you’re looking for strategic advice backed by creative execution. Our Stampa Studio can offer you design and video services for a fully integrated solution.

Public relations

We develop your PR strategy, define communication goals and tactics, identify audiences, formulate messaging, turn strategy into action, and monitor progress.

Internal communications

Whether you need to boost engagement, communicate change, or react to unexpected events, we keep your employees informed, engaged, and aligned with your strategy.

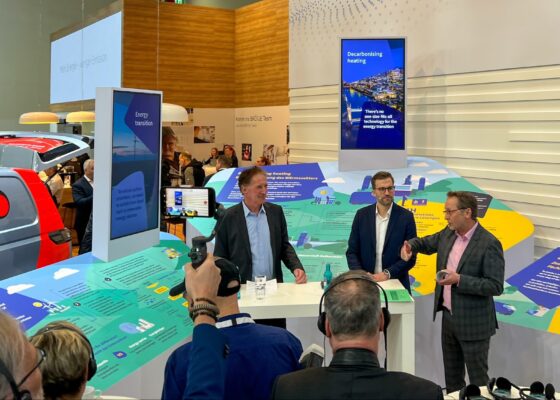

Media training

Make sure you’re fully prepared before engaging with the media. As former journalists, we help you safely navigate media opportunities and shine in the spotlight.

services

The Stampa full-service approach

PR strategy & execution

We work with you to define a clear strategy, set goals, identify your audiences, formulate messaging, manage execution, and monitor progress.

Strategic content

We craft content that brings your strategy to life and engages your audiences across multiple channels, internal and external.

Sustainability communications

With the energy transition and ESG top of many of our clients’ communication priorities, we help you tell a compelling sustainability story.

Stampa Studio

With video and design, our studio team creates powerful visual assets, giving you a fully integrated, strategic-to-creative service.